Thinking Critically About Experiments: Correlation vs Causation (8+)

This is the grade 8+ (ages 13+) version of this lesson. There is also a grade 4-7 version on the site.

![]() If you'd like to have someone read this lesson for you, click play below.

If you'd like to have someone read this lesson for you, click play below.

So far we’ve talked about how to collect new information, and how to test ideas. These are both tools to test your hypothesis. You have a guess, and you make a test to find out more. But what happens if your hypothesis is bad? That can also cause a lot of problems.

In this lesson we will talk about how to make good hypotheses, and how to avoid being tricked into making bad ones.

Causation

We naturally try to find patterns in our lives. This is how we understand the world. One of these patterns is causation. You’ve been doing this all your life without thinking. For example:

If you eat a lemon, it creates a sour taste in your mouth.

You think that the lemon is the cause of the sourness.

If you injure yourself, you will feel pain.

You think that injury causes pain.

If you don’t sleep, you get tired.

You think that lack of sleep causes tiredness.

This is pretty easy right? When something happens, it causes something else. The problem is, we are easily fooled into making bad assumptions about what may cause something else (causation). We often see causation when it isn’t there. Let’s look at a real life example.

Night-lights cause bad eye-sight?

1 - A study compared two groups of kids. One group used night-lights when they slept. The other group did not.

2 - Then the study looked at whether these kids had bad eye-sight when they were older.

3 - Kids that used night-lights had bad eye-sight, compared to the group that did not use night-lights.

4 - Therefore night-lights cause bad eye-sight

Or more simply:

1 - If you use night-lights, you are more likely to grow up and have bad eye-sight.

2 - Therefore night-lights cause bad eye-sight.

Let’s just tell you right now: this is completely wrong. Night-lights do not cause bad eye-sight. But a lot of people (a lot of important scientists even!) thought this was true.

The tricky part is that the research was all correct - children with night-lights are more likely to grow up having bad eye-sight. This is true even today. That part is completely correct and accurate.

The problem is in the hypothesis… or the “therefore” part. People saw causation where there wasn’t one. It turns out that night-lights don’t cause bad eye-sight. Let’s look at this again:

1 - When kids use night-lights, they are more likely to grow up and have bad eye-sight.

2 - Therefore night-lights cause bad eye-sight.

If you’re confused, don’t worry. Adults get confused too. There are a lot of different ways to look at the same thing, and we often get fooled. This is because a lot of things can be correlated, without being a cause. We’ll explain this next.

Correlation

When two or more events occur at the same time or appear to be related to each other, they are correlated. However, just because there is a correlation, it doesn’t mean there is causation. Let’s look at three different ways that correlation doesn’t equal causation, and how you can end up making bad hypotheses.

1 - The cause is the other way!

Here is our first (probably) real-life example:

Wearing shorts causes hot weather.

1 - When you wear shorts, it is hot outside. (correct!)

2 - Therefore wearing shorts causes hot weather. (wrong!)

Unless you have superpowers, this is completely wrong. When you wear shorts, you won’t make winter suddenly turn into summer weather. Wearing shorts and hot weather are correlated, because they happen at about the same time - but that doesn’t mean wearing shorts causes hot weather. In fact (as you already know), it’s the other way! Hot weather causes you to wear shorts!

2 - There is no correlation. It’s a fluke!

Here’s another real-life example:

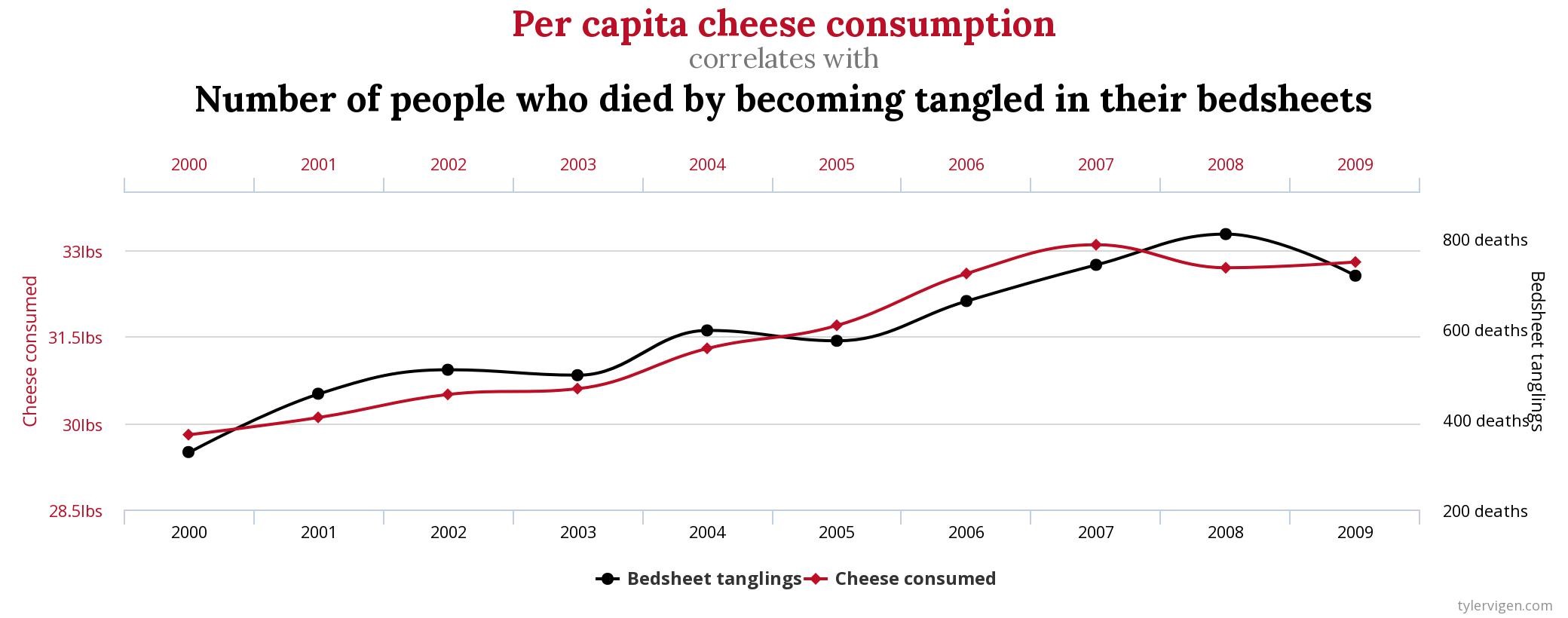

Cheese will cause death by bedsheets.

1 - When cheese consumption goes up...

2 - So do the number of people that die by becoming tangled in their bedsheets!

3 - Therefore eating cheese causes death by bedsheets.

This is a real chart with real data. Notice that whenever cheese consumption goes up, so do deaths by bedsheets. Graph and data courtesy of Spurious Correlations at tylervigen.com

Here is a real graph with real numbers. If you look at the cheese consumption per capita in the United States (basically, the amount of cheese that the average person consumed in the United States), and compare it to the number of people who died by becoming tangled in their bedsheets, they look like they are correlated. So... if you eat cheese, will it cause death by bedsheets?

You better stop eating cheese if this were true.

We all know it’s not true though. This is completely ridiculous. So why does the graph look like there might be at least a correlation, if not a causation? While we don’t know exactly why, but the most likely reason is that...this is a complete fluke! These two things have nothing to do with each other. It’s a complete coincidence. This actually happens more often than you might think.

There are many ways to look at things. Just because things look related doesn’t mean they are. Sometimes they just look like they do, but they have nothing to do with each other. In this case, it’s kind of obvious. Cheese and blanket deaths don’t have anything to do with each other (so you’re safe to keep eating cheese). It’s not always so obvious though.

3 - There’s an entirely different cause!

Here’s our final real-life example.

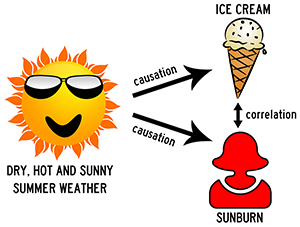

Ice cream causes people to buy sunscreen

1 - When people buy ice cream, the sales of sunscreen goes up.

2 - Therefore eating ice cream causes people to buy sunscreen.

You can probably figure out why this is wrong. Ice cream doesn’t make people buy sunscreen. But sunscreen doesn’t make people buy ice cream either. It’s also not a complete random coincidence - there is a correlation here. Instead, when it’s hot and sunny outside, people like to eat ice cream and buy sunscreen. However, notice that neither the sun, nor the hot temperature are mentioned anywhere in this:

Ice cream causes people to buy sunscreen

1 - When people buy ice cream, the sales of sunscreen goes up.

2 - Therefore eating ice cream causes people to buy sunscreen.

This is an example of someone not noticing that the cause is elsewhere. The two things they are looking at - ice cream and sunscreen - are correlated, but the cause is something entirely different - the hot weather and the sun!

So about that night-light...

Now that you’ve learned the three most typical mistakes, what do you think was the mistake the night-light study made?