Global Inequality: Lack of Funding & Poverty

According to UNICEF, underfunded government public health systems – and too few trained staff - mean children living on the streets in poverty or in remote regions of the world don’t get vaccinated.

Lack of funding (money) is one of the primary causes of global vaccine inequality.

Vaccines rely on a broad network of groups and individuals to get them to the people who need them. This means that if any part of the network doesn't have enough money, there may be people who are unable to get immunized. Let’s take a look at some of the points in the vaccine creation and delivery network that require funding:

Vaccine Research and Production:

It’s important to remember that vaccines have an economic cost. It costs money to research vaccines and make them. This means that if there isn’t enough funding for vaccines from its citizens, governments or donors like UNICEF, there may not be enough vaccines for everyone.

Public Health Facilities and Geographical Challenges:

Most vaccines need to be administered (given to you) by trained health workers, such as doctors and nurses. This means that if there aren’t enough doctors or nurses, it can be very difficult to give vaccines to people. It also means that if you live far away from health facilities where there are doctors and nurses, it can be extremely difficult to get vaccinated. In fact, for some people living in remote areas, the closest doctor or nurse or healthcare facility could be hours, days, or even weeks away.

Unfortunately, some people also don’t have access to a car, or public transportation. Sometimes there aren’t even roads where they live. If you are unable to walk/stand, or have difficulty seeing and hearing, it can be even more difficult or seem impossible to get immunized.

Delivering Vaccines and the Importance of Cold Chain:

Getting vaccines to remote areas presents another problem: in order for vaccines to work, they need to stay cool, (typically between 2-8 degrees Celsius). This means that when vaccines travel in airplanes, ships, cars, or even by foot (walking), they need to be in a temperature-controlled container (such as a refrigerator or a portable cooler). Keeping vaccines at the right temperature all along this chain of distribution and shipping events is called maintaining “cold chain”. If the chain gets broken by having the vaccine exposed to a higher temperature, it can get spoiled and might not work anymore.

This limits the range of how far a vaccine can travel, even if you can get a healthcare worker to travel closer to remote areas. If you live in an area without roads, you can’t use a refrigerated truck. If you have to carry them by foot, there’s only so many vaccines you can carry by yourself.

Watch these two short videos and to see the lengths to which some health workers go to vaccinate children in some of the most remote places on earth!

In Chad, a large country in Africa, vaccines take a long journey to save a life:

Mothers React to a ‘vaccine’ they did not expect:

Poverty and the “Poverty-Trap”:

The last part of the vaccine delivery network is the person getting the vaccine (and their family). Even if all the previous parts have been funded, it is very difficult to get vaccines to those suffering from poverty. There are people living in povery in every country in the world, including here in Canada.

Watch this video from UNICEF of two South African mothers trying to get their children vaccinated. After watching, ask yourself, how could poverty lead to unequal access to immunizations where you live?

A Story of Two Mothers:

Poverty can make access to vaccines very difficult. If the mother could afford a car, maybe she could have arrived at the clinic before the vaccines ran out? Or if the mother could afford a private family doctor, maybe there could have been a vaccine reserved for her? People living in poverty are often more dependent on public services, so if those services (such as public transit, public healthcare) are not adequately funded, they are not able to get access to vaccines.

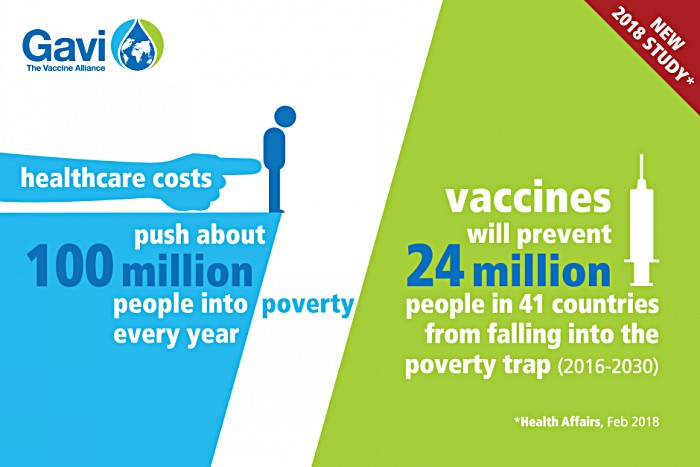

Places where extreme poverty exists can make this problem even worse, and create what’s known as a “poverty trap”. The Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI) – has referred to this as a situation where people are “trapped” in poverty. Being poor makes it difficult to stay healthy, and being unhealthy makes it difficult to get out of poverty. For example:

- When you are poor, it is harder to get access to vaccines.

- If a child can’t get vaccinated, they are more likely to get sick.

- A sick child can’t go to school

- A sick child needs healthcare and medicine, which costs money.

- A sick child needs care, so some parents may stay home instead of earning money.

- If the family can’t afford medicine, they might have to sacrifice other things to save money. This is often done by not buying food and skipping meals.

- If the family doesn't eat, they are more likely to get sick, including the child. A hungry child is also less likely to do well in school.

- A sick child won’t get the same amount of education as a healthy child, so they won’t be able to get a good job when they grow up.

- Without a good job, it’s hard to escape poverty.

- When you are poor, it is harder to get access to vaccines.

Notice how step 1 and 10 are the same. When you start with poverty, it is easy to end up where you started. How would getting vaccinated help stop this cycle?

This would make a great poster – try making one for your class!

According to the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), we can estimate the number of people that have been unable to escape poverty due to various vaccine-preventable diseases:

- Hepatitis B - 14 million people

- Measles – 5 million

- Meningitis A – 3 million

- Rotavirus – 242,000

This infographic from GAVI shows how vaccination can prevent people from falling into the poverty trap. 24 million people is a lot! Imagine how many more we could prevent if everyone could get vaccinated?